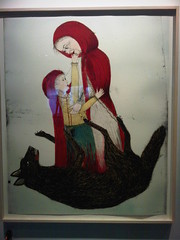

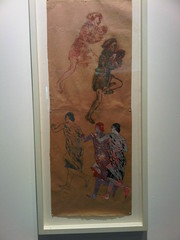

I finally made my way to SoHo to view the Jeff Koons curated Skin Fruit. Now that I can say that I have seen it, I have leave to air my own grievances. The provenance of the exhibition leaves me with an icky feeling too, just as all those who have decried the New Museum since the show was announced. If you are unfamiliar with the ethical controversy on how the entire exhibition was culled from the personal collection of New Museum Trustee and Greek-Cypriot contemporary art-accumulating billionaire Dakis Joannou, there is a good primer at Art Fag City. Koons could have shut up all of his critics if Skin Fruit was a grand slam; alas, it is quite the opposite. Joannou’s collection is vast, and Koons selections from it make both he and his ur-patron appear to lack any discretion in taste whatsoever.

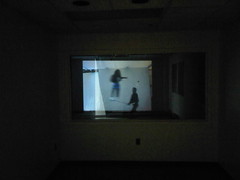

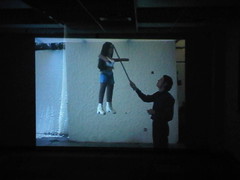

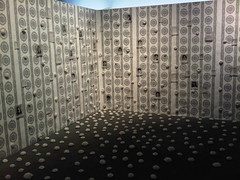

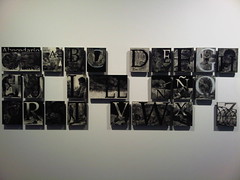

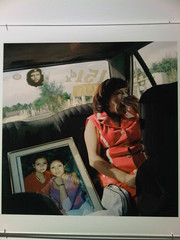

Photographs cannot do justice to just how chaotic it feels inside of the galleries (see Vernissage TV’s video tour for a better idea). I can only imagine that this is an unfiltered peek at what the inside of Koons' head must look like: dozens of giant, clashing ideas clawing their way out, wreaking monkey business along the way. Remembering what it looks like in his studio (from the TateShots clip below), I cannot say that I am surprised. To be upfront, I am an admirer of the man in various ways; however, this is not his finest moment.

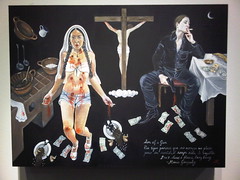

Briefly, the fourth floor is a catastrophe, the third floor is poor, the second floor is kind of okay, and the small gallery on the first floor is all but unremarkable. There were some bright spots for me, such as the Robert Gober room. Overall, I believe that the problem is that any excellent artwork is drowned out by the big, bad, bombastic artwork; the exhibition becomes only as good as its weakest, most crass links. By way of example, the inclusion of two Paul McCarthy sculptures, when really one would have been more than enough. How about the bullying dominance of Roberto Cuoghi’s Pazuzu over the entire fourth floor gallery?

The other day I found myself silently judging someone who was raving positively about Skin Fruit. This individual singled out Tino Sehgal’s security-guard-singing piece This Is Propaganda as an example of its greatness. Am I wrong to feel this way? I resolve to sleep comfortably.

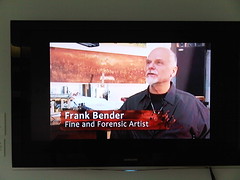

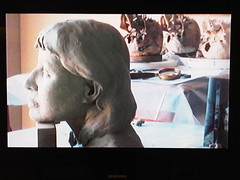

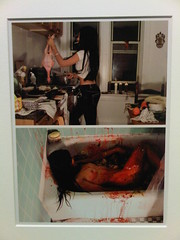

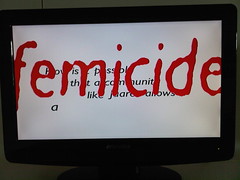

But the expedition to Bowery was not all bad. At about 11:45, while I was standing outside, waiting for the doors to open, who did I see but Matthew Barney and Björk also waiting to be admitted? They get special treatment at MoMA in order to be able to sit with Marina Abramović, but not at New Museum: they have to wait along with the unwashed masses! It happened that there was a weekend-long symposium going on, of which I was lucky enough to catch about an hour. I saw Gabe Bartalos speak, makeup and special effects artist artist for the Cremaster cycle and Drawing Restraint 9, as well as numerous B-grade horror flicks as Leprechaun and Frankenhooker. The subject of that day was creating images of death. He showed clips of his work and gave insight into his behind-the-scenes process. In speaking about the sculptural nature of his art (i.e. things like the cast latex or synthetic pieces used to simulate wounds), Bartalos described how excessive use of fake blood can be a way that makeup artists hide imperfections in their work; to him, “Blood or goo are the curtains on a really nice house, which sits on a really great foundation.” How cool is that?