The Bruce High Quality Foundation have responded to my post critiquing their Teach 4 Amerika stop in Philadelphia. Please read the full text here:

http://teach4amerika.org/uncategorized/if-funding-art-is-wrong-we-don't-want-to-be-right

I was thrilled with their response, even though I still think they are off base. Below is my reply, also posted in the comment section of their blog post:

First of all, thank you for engaging with this topic and taking the time to respond to my critique. I am also glad to hear that I am not the only one who voiced a concern of a similar nature. I could not agree with you more that to be an artist and to present art for the right reasons is a moral imperative. But what I was reacting to in my original post was the impression that I got from your presentation that even mentioning money or economic value is to denigrate the arts in some way, which I thought was either naïve utopianism, to lift one of your descriptors, or textbook contrarianism. You seemed to be more interested in subverting the existing systems that you felt had done wrong by you, rather than trying to improve or repair them, in your advocating for the type of antiestablishment model that BHQFU represents. I found this attitude unhelpful to a larger public and ultimately self-serving.

Now it seems that you acknowledge the importance of public funding for the arts, even though chasing after and distributing public funds for the arts is a labor-intensive process fraught with agonizing bureaucracy, and the recent federal budget battles mean the outlook for the NEA and NEH is hopeless. Are you asking: why even bother? It is not necessary for me to debate with any of the Tea Party/Conservative devil’s advocate playing here, because I know that this is not what you believe. In my own idealist fantasy, public funding the arts would never be looked at as a political issue or a superfluous luxury; it would be universally accepted as providing access to a basic human right.

However, I fully embrace that our free market system means that corporations and individuals can contribute to the arts at the highest level they choose, make stipulations for the use of the money, and demand to be acknowledged in a certain way. I concede that I am a Development person, so something like Target Free Nights (we have these in Philadelphia at the Franklin Institute, too) does not bother me in the way it may rankle you. It is an outward signifier that the leadership of the Target Corporation, or any company that sponsors an event or series, sees the value of the arts and makes a commitment to culturally enriching the lives of people in places where it maintains a business presence. I am not naïve enough to think they are doing it for nothing. They have a right to want people to be aware of their contribution, just as a person who gives money to endow a curator position or pay for a new museum wing wants his or her name in the title. I do not have a problem with this; I do have a problem with an institution accepting money that may have ridiculous reporting guidelines, strings attached that hobble the fulfillment of mission or lead to “mission creep,” or specifically support a program that inordinately benefits the gifting entity. I also disagree with accepting money from a company that has a poor public image or reprehensible corporate values (e.g. BP).

It is not wrong to lead the fight for the arts with the economic argument. You astutely mentioned that in the halls of Congress, the economy has taken precedence over all other debates. Citing the model of the arts as an economic stimulator gets a foot in the door with officials who want to know what good this will do to helping their constituents and to getting themselves reelected. It does not stain the nobler elements of the arts to report on well-researched data that demonstrates the substantial financial impact that the arts generate in a community. The economic imperative is the tactic that works today; the “Great Nation” claim that inspired the NEA’s creation, though still credible, is no longer compelling to those in a public arena. You do not have to soil your hands with championing the economic effects of the arts if you do not want to do so; leave that to arts administrators and arts advocates. But do not reject us outright, because we share motives and goals that have everything in common. If I did not think that the arts are the most fundamentally important thing in life besides physiological human needs, there is no reason that I would be in this profession.

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

Monday, April 11, 2011

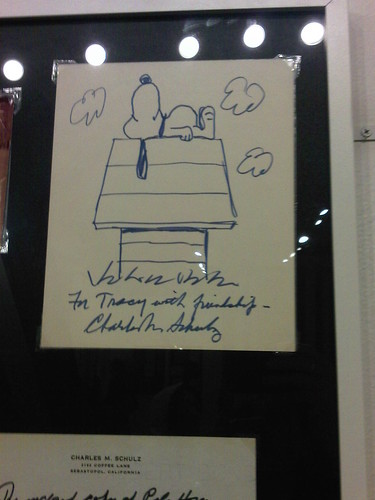

The Lives of Charles M. Schulz

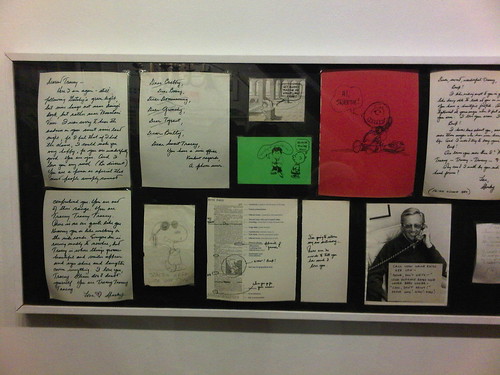

This is a Love Letter: Personal Correspondences from Charles M. Schulz, which spans art, artifact, and ephemera, is unlike any other show I have seen at Space 1026. The title explains the basic premise, but more on that later. It also brought out a more age-diverse crowd than any Space 1026 opening I have witnessed, no doubt due to the interest in Schulz and his Peanuts gang. It was an affirming feeling to see young and old enthralled by these letters. At a moment when omnipresent media force-feeds us predigested junk at a hysterical rate, a character like Charlie Brown can still be a reliable and satisfying staple. There is something incredibly centering about taking delight in these classic characters; for me, it elicits memories of my grandmother, and her love of Snoopy in the funny papers.

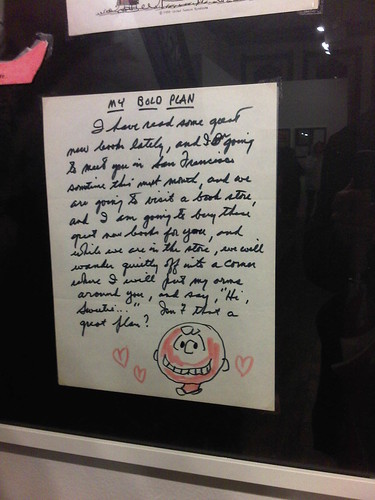

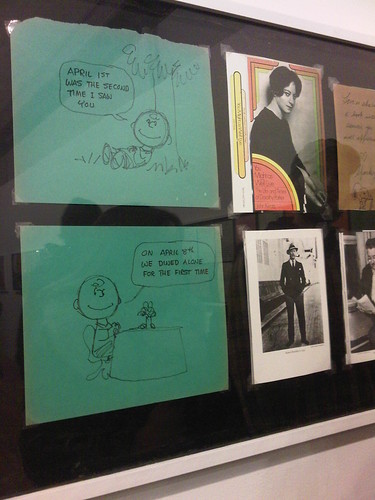

At face value, the letters tell the rise and fall of Schulz’s (or “Sparky,” as he was known to all) love for a young woman named Tracey Claudius in the early 1970s, who was a Philadelphia resident. His prose is romantic to the core, unabashed in letting emotion overflow as he writes repeatedly about his unquenchable and constant desire to see, speak, and be with her. Superlatives abound: his love for her is the strongest and she is by far the greatest. Doodles of Charlie Brown and Snoopy, as well as other one-off characters not among the Peanuts, punctuate some of the letters. Any woman would feel elated to be on the receiving end of such tenderness and constant attention.

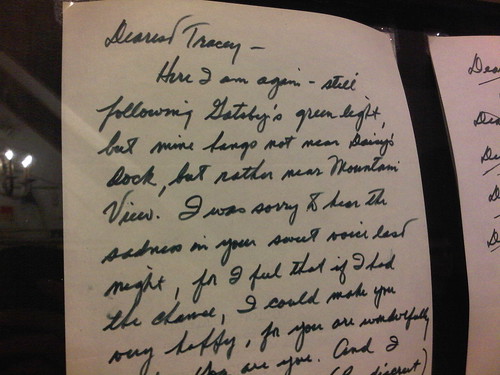

But hidden in plain sight, the letters offer a far twistier story. The collection is effectively presented as is, without much curatorial guidance. A crucial detail goes unspoken: that Schulz carried on his affair with Claudius while he was still married to his first wife (source.) In a telling passage, he writes of “following Gatsby’s green light.” The connotation, taken in context with the rest of that particular letter, would seem to be that Schulz is simply a hopeless romantic; however, comparing himself to the doomed Gatsby, with his unrequited love for Daisy, does not foretell good things to come. If anything, Schulz was something like shades of Jay Gatsby (to his lover and as a cartoonist) and Tom Buchanan (to his wife and others) rolled into one.

Where Charlie Brown and Snoopy pop up in the letters, they act as stand-ins for Schulz’s fragmented psyche, the different parts of an outward persona that he had cultivated. Charlie Brown still plays the loveable loser, blissfully living in the moment and unbothered by worries of a love affair that can have no future. Snoopy, on the other hand, is roguish and consciously detached; the iconic Snoopy alter ego “Joe Cool” appears in a sketch placed near a photo of a smiling Schulz talking on the phone. Who was the real “Sparky”? Both elements, the starry-eyed lover and the smooth playboy, persist in the letters.

Does Schulz’s flawed personal life besmirch Peanuts? Of course not. Attempting to understand him adds depth to his already staggering oeuvre. In coming up with ideas for a daily strip that ran for fifty years, correlation between the man and his art was inevitable, for we write (and draw) what we know. If Peanuts ever seemed uncomplicated, there was so much more bubbling beneath the surface than we ever perceived.

Monday, April 4, 2011

The Bruce High Quality Foundation’s Teach 4 Amerika – An Arts Administrator’s Perspective

Last week I saw the Bruce High Quality Foundation’s Teach 4 Amerika at Tyler School, and their presentation has unsettled me since. Philadelphia was only the second stop on their breakneck, month-long tour of art schools across the United States in a repurposed limousine/school bus. The tour is aimed squarely at people with BFAs or MFAs (or those who are currently pursuing them) and art school faculty. As an Arts Administration graduate student, I was undoubtedly in the minority of those present. But the BHQF presenter called out arts administrators, particularly those who run art schools, and I feel a response is appropriate.

I first became aware of the Bruce High Quality Foundation last year when their piece We Like America and America Likes Us was included in the 2010 Whitney Biennial. The work consisted of a Joseph Beuys-referencing (or was it Ghostbusters-referencing?) Cadillac Miller-Meteor ambulance, with a video rear-projected onto the windows. The video stitches together iconic film footage, viral online clips, and snippets of news and popular culture, over which a narrator speaks. The piece nails the melancholy and longing of Millennials whose contemporary reality is that we live in an America which was forged through hardship by the Greatest Generation and then laid to waste by the Boomers.

The Teach 4 Amerika presentation is really no different in its tone. The crew at BHQF are very clever, almost too clever, in their manipulation of appropriated media and pairing image with message. A recurring motif is the use of clips from One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest to illustrate the absurdity of the present art school ecosystem. The narrative is built around the story of an archetypal girl who is pursuing her BFA at MICA. You see, BHQF have a bone to pick with the business and economics of art and art schools. It is hard to begrudge them that the commercial art world has its unseemly practices. It is also fact that almost no one who graduates with a fine arts degree will achieve gallery representation, let alone sales robust enough to support a living. But for they would have it, it’s ars gratia artis or nothing. Art is a vocation, a higher calling—a point that I can agree upon—but one which is sullied once money becomes involved; art and business are at polar ends of the spectrum.

BHQF takes exception with the National Endowment for the Arts, picking on its leader Rocco Landesman (an easy target), and its current tagline “Art Works,” i.e. the concept that art can be a generator for local economies. In this city, such a claim is tantamount to blasphemy. Alas, there was no one from the Office of Arts, Culture, and the Creative Economy, the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance, or the Arts & Business Council to go toe to toe with them. At the least, their bone of contention with the economic argument for the value of the arts is appallingly naïve. It is the most formidable tool that those in the arts have against naysayers, particularly elected officials who fundamentally disagree that public money should be used in support of the arts. It is but one part of an arsenal that encompasses and can work hand in hand with arguing for the intrinsic value of the arts, not its mortal enemy.

The tour amounts to little more than preaching to the converted, pandering to manifest frustration about feeling saddled with debilitating student loans to earn an art diploma that will not lead to a sustainable job that can employ the skills learned while obtaining said diploma. BHQF poses many questions but offers no solutions, other than that they have founded BHQFU, a do-it-yourself “university” for people who want to take part in a creative community (they also reject the accreditation system for art schools as another micro-economy that only looks out for its own monetary interest).

Teach 4 Amerika is hipster venting, styled as earnest exploration of critical issues. If it is all a put on, a grand work of performance, BHQF is bamboozling susceptible minds. If they are for real, and represent a truism about the future leaders of our arts communities, all of us are in trouble.

Saturday, April 2, 2011

Soil Kitchen

Yesterday evening I attended the opening reception for Soil Kitchen, a temporary public art project organized by the City of Philadelphia Office of Arts, Culture, and the Creative Economy. The collective Futurefarmers—unanimously selected by a panel including Carlos Basualdo, Joshua Mosley, and Winifred Lutz—provided the artistic vision, drawing upon Don Quixote, whose statue stands across the street from its location at 2nd Street and Girard Avenue. They appropriated the windmill, but as a positive model for sustainability and clean energy, rather than the imaginary enemy of a knight-errant. It is tempting to invoke the namesake quixotic moniker, but the project provides a model for community engagement necessary for transforming a dream and an ideal of sustainable living into a practicable reality.

The concept is simple and anyone can participate: bring in a soil sample for analysis and receive a bowl of soup in return, made from fresh, local, and organic ingredients. Empowered with the knowledge about the health and quality of their soil, participants can then take the leap to growing their own vegetables, which can become the ingredients for their own sustainable food.

Visit Soil Kitchen before it closes on April 6!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)