I drove up to New England to see my parents over the long Independence Day weekend. Whenever I go, I try to hit as many museums as possible, but inevitably I must narrow my focus to a select few that I particularly want to see on that trip. This time, The Aldrich Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut was at the top of my list. One of the things I love about The Aldrich is that it is exactly the right size. The museum presents exhibitions which are consistently manageable in scale and always of high artistic value. You could spend two to three hours at The Aldrich, experiencing each exhibition very thoroughly, and you would leave not feeling overwhelmed. I have found it to be a rather refreshing place to visit.

Currently, the atrium is perforated by Gina Ruggeri’s cavern-like wormholes, which belch sinister clouds of gas—painted Mylar decals adhered to the walls.

The eponymously-titled KAWS was the main draw for my visit. KAWS (real name: Brian Donnelly) is based in Brooklyn, though apparently he is of much better renown in Japan than in the United States. You will have seen at least one of his designs; he created the cover for Kanye West’s 808s and Heartbreak.

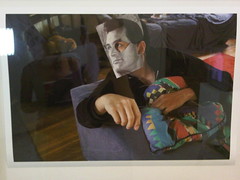

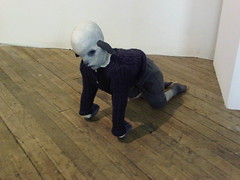

Should I try to classify the work? Is it street art? Design? Pop art? Appropriation art? Wholesale rip-off? The only proper way to describe it is as a buffet of assimilation and subversion. The artist is obsessed with popular cartoon culture, altering iconic characters in such a way as to unsettle the firmly-set image in the mind’s eye of the viewer. For example, he starts with the Simpsons, “X-es out” their eyes, adds goofy skull teeth and grotesque ear-like growths, and calls them the Kimpsons. But these mutations do not feel like cruel potshots at images that the inner child fondly treasures. When KAWS looks at these cartoons, he must see something entirely different than most of us see. Could he simply be aligning what he perceives, to match what the outside audience will see? I do not consider these works to be incisive commentary on cultural touchstones like Mickey Mouse or the Michelin Man. I believe this to be KAWS’s way of cherishing these same characters we all love. Through repetition of the same characters, with slight variances each successive time, he has built his artistic lexicon.

![KAWS - Untitled (Kimpsons) [detail]](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4078/4759446582_d24a08e9e4_m.jpg)

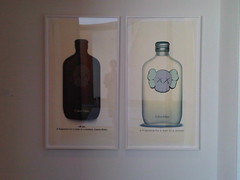

I enjoyed his advertising-based works the most, where he paints directly onto the ad. The sight of a slithery creature winding around Kate Moss was both disquieting and delightful. The inherent dichotomy is that he has taken something so overtly commercial and, with a few judicious strokes, inverted it into something equally commercial in a market which began underground, but is now mainstream. His early bus shelter posters, typified at The Aldrich by Calvin Klein perfume ads, became highly sought after commodities, with collectors snatching them right off the streets. His figurines and statues are prized and expensive collectibles. And he has extended his brand by providing designs to the purveyors of shoes, snowboards, and other merchandise. I am guessing his original intention as a guerrilla artist was a bit more radical, but KAWS was shrewd to embrace saleablity when market demand, instead of running from it, when interest in his work exploded.

![KAWS - Untitled (collaboration with David Sims) [detail]](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4134/4759447830_4541cc4d16_m.jpg)

![KAWS - Untitled (collaboration with David Sims) [detail]](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4077/4758811149_c52d7c5360_m.jpg)

![KAWS - Untitled (collaboration with David Sims) [detail]](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4078/4759447962_d6930ac151_m.jpg)

![KAWS - Untitled (collaboration with David Sims) [detail]](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4122/4759448268_5e94f25e6e_m.jpg)

On the second floor, the exhibition Gary Lichtenstein: 35 Years of Screenprinting was a feast of gorgeous artist edition prints. Lichtenstein ran a studio in San Francisco, and then later in Connecticut, where for decades he has made prints for widely-known artists. The designs on display are not his own, but the art and practice that has brought them to life are solely to his credit. Through his use of color, Lichtenstein puts a direct stamp on the prints he produces. Some pieces use dozens of colors, a labor-intensive process, each requiring a discrete pass of pigment. Shelves had been built into one gallery wall to house a collection of used ink cans. I was completely taken with the signature touches in the way the show had been designed and installed. The introductory text panel was actually exposed onto the emulsion of a silkscreen, which was then made legible by squeegeeing dark ink through the mesh. The banal formality of the introductory text in a museum exhibition is a given, even when it communicates interesting information; to see it presented in such a innovative and sensitively subject-specific fashion jolted my expectations in the best way possible. The exhibition had the true feeling of a print studio, from the screens, to the drying rack loaded with artist proofs, to the wall of pigments. As a means of bringing the audience closer to the artist and his work, the exhibition succeeded in every way possible.

I cannot neglect to mention Beryl Korot: Text/Weave/Line—Video, also on the second floor. In her recent works of video, Korot weaves together word and image into a kind of multimedia textile. These represent a natural evolution from her work Text and Commentary from 1977, also on display, where she stages a row of televisions broadcasting extreme close-ups of textiles, the zigzagging patterns of which she has mirrored with graphite on paper grids, all divided by a screen of hanging fabric bolts. Korot was an early adapter of portable video technology and a pioneer in video art.

![Clint Baclawski - Motorola [left] & The Titanic [right]](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4099/4781238188_8882933a4e_m.jpg)

![Nora Salzman - Replica Reuben [foreground] & Replica Reuben Masking as Nora [background]](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4117/4780604631_1e6b929bf5_m.jpg)

![Sally Denison - Ingrid [left], Hannah [center], Theresa [right]](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4074/4780609357_733ed24fe1_m.jpg)

![Dustin Metz - Still Life [left] & Self Seeing Portrait [right]](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4142/4781242458_9a79f9108c_m.jpg)