São Paulo may be the undisputed capitol of street art in Brazil—if not the world—but Rio de Janeiro is no slouch by comparison. Graffiti is ubiquitous, whether in the poshest or most marginal areas of the city, like a visual leitmotif with give-and-take relationship to urban life in Rio. Before my most recent visit, I attempted to educate myself as much as possible about the local scene. The book Graffiti Brasil by Tristan Manco, Lost Art, and Caleb Neelon, became my bible thanks to its information about the history, terminology, styles, and key players in the vast world of Brazilian graffiti (though understandably its focus is on the Paulistano variety). As a reference it is peerless, because there are few published works in English on the subject. In my own writing I realize that I may mangle some of the nuanced distinctions between things such as throw-ups, bombings, and pieces (or murals), while altogether ignoring the confounding debate over street art versus graffiti art.

Graffiti is as integral to the landscape of Rio as the mountains and the sea, and it is everywhere, from locations where it is officially sanctioned by the municipal prefecture, to places where it is an illegal act of transgression. I spent most of my time in Zona Sul, more specifically areas like Lagoa, Jardim Botânico, Gávea, Botafogo, and Ipanema. The more graffiti that I saw, the easier it became to discern the different styles of certain prolific artists. Some works are signed, either by the individual artist or the graffiti crew, but often they are unattributed. It was only after I returned home to do research, especially in the graffiti groups on Flickr, that I identified the artists whose work I had photographed.

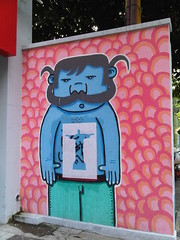

Fleshbeck Crew (usually shortened to FBC) is one of the more prevalent groups. I continuously noticed the work of crew member Toz for his cartoony, cat-like creatures. Road, another member, had also laid claim to many areas with his DJ1 character. In addition to their recognizable characters, I think that the color sensibility of this crew sets it apart, by bringing together blocks of bold, contrasting shades.

Infrastructure provides the best canvas for graffiti art, and the wall enclosing Joquei Clube along Rua Jardim Botânico is a nearly kilometer-long bonanza of countless artists. It is work that has been done legally, disregarding the tags written over some of them (a sign of disrespect), hence the scale and level of detail in these pieces.

The overpass at the northeastern corner of the lagoon is another excellent place to see a great assortment of pieces.

Avenida República do Chile in Centro also has an impressive concentration of work.

I did not see many paste-ups, except for this recurring silhouette cut-out of the Cristo Redentor statue, typically stuck over already graffitied walls.

Pixação (also spelled pichação) is another strain of graffiti, akin to tagging but with very specific criterion. The pichador writes his name, the name of his crew, or the name of his grife (a larger amalgamation of crews). The authors of Graffiti Brasil explain, “There are some visual rules—for example, the letters of the tags should be uniformly tall and wide, meeting an invisible and straight guideline at the top and bottom of the name. The letters should usually be separate from one another. In addition, the breaks and bends of the tag’s letters should (again, normally) be at a consistent elevation (e.g. two-thirds of the way to the top of the letter).” But pixação never stops at a solitary tag; it is a uniform repetition of the same tag at regular intervals. It is most commonly associated with São Paulo, but “in Rio de Janeiro, these spray-painted tags are small, with tight, looping and often symmetrical forms.” Depending on the thickness of the letters, spray cans or rollers can be used. This video produced by Coolhunting is a first-rate primer on pixação.

Pixação is aggressive and nihilistic. It is loathed my most people as the lowest form of vandalism, and its practitioners do not think of it as art. If anything, it is more of a political act, an in your face assertion of personal existentiality by people otherwise invisible to the ruling class. When an entire building has been scrawled with pixação, society cannot ignore it. Most of the pixação I saw in Rio falls into the category of agenda, where street-level walls become filled top-to-bottom with different tags. In the hierarchy of pixação, agenda tags are not well-respected. It is the heaven-spots, e.g. the tops of buildings or precipices where the pichador must actually risk his life to access (watch this trailer for the documentary PIXO to see hair-raising footage of climbing pichadores), that are of high status. Also impressive is when a crew can bomb an entire building. The only such example I saw was in Niterói, but the internet is littered with photos of buildings that have been fully hit.

I found pixação fascinating, rather than odious—perhaps I would feel another way if someone had bombed my building. It takes the dedication of an artist, even though it exists in a no man’s land at the periphery of art. In this regard, I have a sense of respect and awe for the pichadores. I suppose that, strictly speaking, they do not care whether you love or hate what they do, as long as it provokes a passionate reaction.