Rashaad Newsome - Untitled, 2008

Before it gets too far removed from the fact, I have a few more thoughts to share on the Whitney Biennial 2010. I was enraptured with Rashaad Newsome’s pair of videos Untitled and Untitled (New Way). He pulls Ballroom culture out of its natural habitat, having two performers energetically vogue in small, blank rooms. The soundtrack is muted, centralizing focus on the stories that these young men narrate with their balletic movements. This vacuum of extraneous sight and sound strips away any element of camp, leaving only the beauty and art of the physical performance. Though still primarily underground and not seriously respected when compared to more institutionally sanctioned forms of dance, voguing is becoming more visible in mainstream media (think of TV programs like America’s Next Top Model and RuPaul’s Drag Race), so placing it in this museum setting is not as transgressive as some might be tempted to think. Spend time watching both videos in their entirety; they are each under ten minutes in duration, and well worth a dedicated viewing.

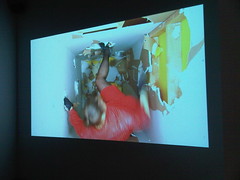

Kate Gilmore - Standing Here, 2010

Kate Gilmore’s Standing Here is another isolation-chamber type drywall demolition derby, similar to what I saw from her at ICA in Philadelphia last year, this time transferred to a narrow vertical shaft setting. Her performances and the accompanying videos are becoming progressively slicker in their production values. I am still digging her work, along with its gender complexities which I will not delve into here, though I must declare that it no longer thrills quite like the unpolished DIY sensibility of earlier projects, such as Anything…, where she builds and then scales a harrowingly rickety tower of furniture, or Main Squeeze, in which she attempts to worm her way through a ridiculously narrow scrap-wood tunnel.

Gilmore's point of entry/escape

Without going into too much detail, here are a few of my other favorites: Tauba Auerbach’s exquisitely bemusing “fold paintings”; Aurel Schmidt’s minotaur, which nicks Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s calling card, substituting cigarette butts, beer cans, and other grimy trash; and the delectable ink-bleeds of Storm Tharp’s portraits.

Piotr Uklański - Untitled (Red Dwarf), 2010 and Untitled (The Year We Make Contact), 2010

Piotr Uklański’s contributions Untitled (The Year We Make Contact) and Untitled (Red Dwarf) are not so much great, or even good, as they are hulkingly inescapable; I was strangely ambivalent about them.

My least favorite pieces were predominantly those with a political bent, whether they championed hope for a brighter future or portended America’s theoretically inevitable demise. Jessica Jackson Hutchins’ Couch for a Long Time, or the “Obama couch”, is unrepentantly partisan; but to me, the greater sin is how corny it feels, simultaneously existing as art comfort food for liberals, anathema for conservatives, and a big “huh?” for centrists. Bruce High Quality Foundation’s We Like America and America Likes Us is something of an open love letter to our nation, ruminating on whether the affection is or is not mutual, that while ostensibly being the work of a younger generation of artists, somehow felt as though it panders more to a Boomer crowd through its selection of appropriated footage and images. I appreciated the Beuys allusion in the use of the vehicle and referential title; though ultimately, I grew cynical of the video component as it wore onward (you can watch the whole thing here). Hung within the same gallery, Lorraine O’Grady’s dueling Charles Baudelaire/Michael Jackson portraits were another dislike of mine. The pop culture topicality of selecting not one, but two MJ referencing works (the other being Daniel McDonald’s gimmicky, smoke-spewing sculpture in the lobby), smacked of a curatorial laziness that felt out of step with the overwhelming majority of Francesco Bonami’s and Gary Carrion-Murayari’s choices for the Biennial.

And for the worst in show? Josephine Meckseper’s stultifyingly unsubtle Mall of America (brief snippet here). I couldn’t take much of its plodding, monochromatically filtered, and ominously clichéd shots of rampant American consumerism, done no favors by a blood-curdling, eardrum-rattling soundtrack. Recurring flashes of “sale” or “discount” placards, shoppers in slow motion, and deafening noise? I get it: America and its rampant consumerism are morally bankrupt, enslaving and ultimately dooming us. Thank you for your “enlightened” outsider perspective (Meckseper is German by birth, now living in the U.S.A). Maybe this unflattering portrayal is how we truly appear to the rest of the world, if not what many of us see when hold a mirror to ourselves. But did I need this browbeating artwork to tell me what I already know? And can it really be possible that the video is almost thirteen minutes in length? Watch thirty seconds of this one and you’ve seen all you need to see.