On my lunch break this past Friday I booked down to the river to see Art In The Open (AiO). The short timeframe limited my viewing to the stretch between Walnut Street and JFK Boulevard (the full span of AiO extended along the Schuylkill from the Water Works to Bartram’s Gardens). At 1:00 pm on beautiful day, traffic was sparse and the feeling was relaxed. Some people were lunching al fresco, and there were only a scattered few runners and bikers, as well as some strolling pensioners. It was nothing like the rush the river path sees on a weekend or after work hours have ended. I got the impression that Art In The Open is better experienced set against the energy generated by throngs of visitors, rather than the calm of a lazy day. There were also numerous participatory classes and events planned for Saturday, which I inevitably missed.

Citing inspiration from the artist practice of working en plein air, one might think that the participating artists are limited to those of an Impressionist-inspired landscape painting persuasion. Indeed, I did encounter some painters out with their easels; with no disrespect their art or methods, watching a painter of this breed in action does not make for a terribly eventful or invigorating spectator sport. Integral to AiO’s concept is to interact freely with the artists and I did observe artists chatting with passersby. The atmosphere is meant to foster free exchange of ideas.

However, the scope is more encompassing of other media. Take the work of Swiss artist Roy Andres Hofer as an example, who interpreted the idea of “open air” artwork via a picnic. Alluding to Édouard Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, he instead offered a picnic spread of processed junk food. The packaged goodies sat sweating in the sun and encircled ritualistically with paper plates, devoid of partakers, like a Día de los Muertos grave offering. In another picnic referencing work, I came across Harry Bower’s Earth Blanket, which was woven from the plastic belts used in classic-style folding lawn chairs.

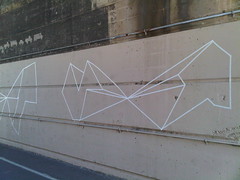

The most intriguing project I viewed was Polygon Blooms, a collaboration of Benjamin Volta with Jerry Jackson and students from Grover Washington, Jr. Middle School. Ensconced beneath the umbrage of the Market Street bridge, it consisted of a sculptural work mirrored by geometric shapes on the opposing wall. What I liked most about Polygon Blooms was the use of environment. Undersides of bridges, forgotten spaces in plain sight, conjure all kinds of pithy imagery—society’s marginalized people, graffiti encrusted walls.

Okay, so this is not nearly the first art project to take place under a bridge. But it was a pronounced contrast going from the conventionality of artist painting in the manicured park-like landscape along the river path, to the minimalistic delights of geometric forms traced over the raw and slightly shabby industrial understructure of the bridge. The polygons were absolutely transformative to the space, drawing beauty out of—or at least on top of—a concrete wall. The ephemerality of medium, simple masking tape, made their existence all the more precious.

Art In The Open should continue as an annual event, growing with passing years in breadth and ambition. What I hope will cease is an apparent trend of mining ideas from Nineteenth Century Paris. Without question, it was one of many cultural pinnacles for western art. But I do not think that my eyes could roll back further into my head if once more I hear anyone say that we strive for the Benjamin Franklin Parkway to become like the Champs-Élysées. And now arrives AiO, with the idea of art en plein air as its thematic crux. I have always regarded the notion of American Impressionism to be misplaced; Impressionism was French to the core, expressing a concept of modernity for that particular environment and era. This is Philadelphia—nowhere else—and it is one decade into the Twenty-first Century. If anything, we should look to American models for inspiration and reinterpretation. We have a youthful population and a wellspring of limitless ideas on our side. Our ideas for the future, while not being ignorant of the past, must push ahead, deriving identity from our own character, surroundings, and place in time.

No comments:

Post a Comment